Thirty years ago, my husband and I, tired of the ever-grey skies of the Netherlands, booked a December driving holiday in Andalusia. We toured Seville, Cordoba and Granada. I loved all three, and that is when the seed of our dream of spending winters in Southern Spain was planted. I have seen many palaces and castles since then, but Granada’s Alhambra always stood out in my mind, so this year we decided to return with our son and his girlfriend, who are visiting us from Sweden.

Alhambra — one of the many courtyards

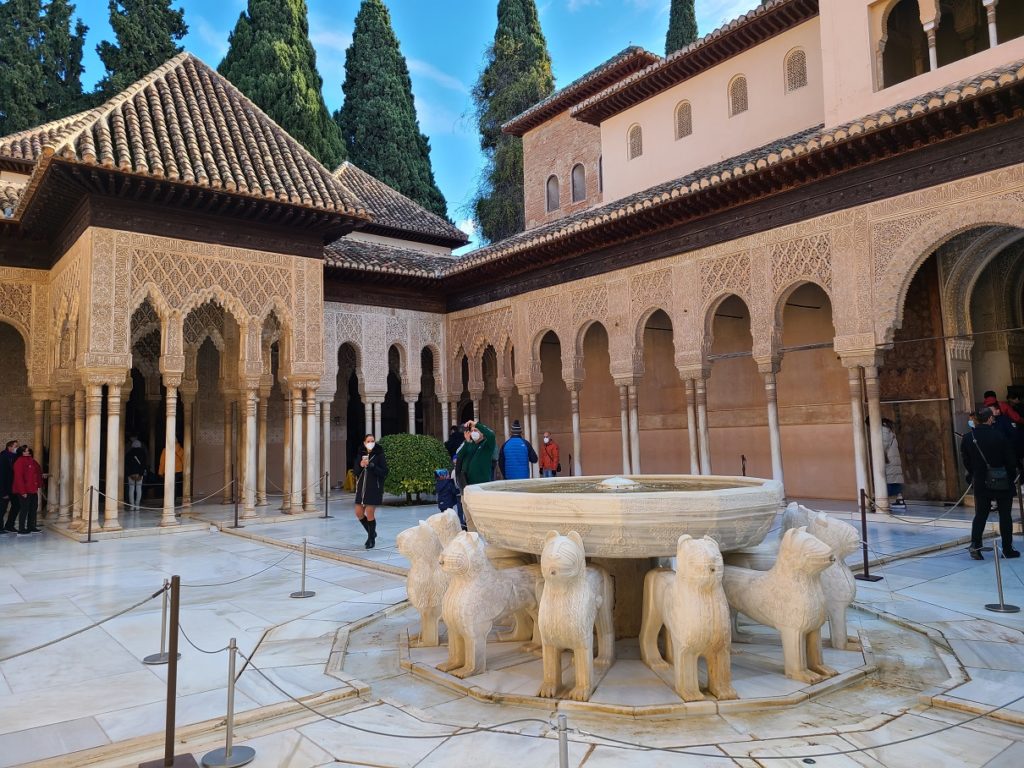

Courtyard of the Lions, Alhambra, Granada

A quiet hallway in Alhambra

Between Covid rules and the sheer volume of tourists, getting inside was an ordeal, and the Alhambra didn’t have quite the magical feeling it did when we were able to see it without the throngs of masked tourists (and guards patiently reminding them that they have to keep their masks on even for photos!). Nevertheless, it is still an impressive sight. The amount of detail and decoration is truly outstanding, and the setting is lovely.

After touring the palaces and gardens we decided to check out the “Jewish” quarter, the Realejo. The centrepiece of the so-called Jewish district is a statue of famously antisemitic Queen Isabella granting a royal charter to Christopher Columbus.

Jews are believed to have first settled in Granada after the destruction of the 2nd Temple in Jerusalem in the year 70. (There is somewhat stronger evidence placing Jews in Granada by 135, but why quibble?) By the time the Muslims came in 711, it was known as “Granada of the Jews” (Garnatha al Yejud or غرناطة اليهود).

The Jewish population thrived under some of the Muslim leaders. Yehuda Ibn Tibon (born 1120), for instance, was a famed poet, philosopher and translator of many of the classics and of Arab scientific works. His family founded Granada University’s school of translation, which developed a global reputation. One of the very few traces of Jews in Granada today is a statue his descendants put up in his honour in 1988, a block away from the homage to Isabella and Columbus.

I saw on Google that there is a Sephardic Museum in Granada, so we set off to find it. It was already after dark, and the map was leading us up narrow, empty, back streets. DH was getting nervous, thinking we’d set ourselves up to be mugged. But we persisted, and finally found the door to a house with a sign indicating that we were in the right place. There was a sign on the door saying visits were by appointment only. Through the open, grate-covered window, could see a woman sweeping up so I asked if we could visit. She explained that it was dinner time, but let us in anyway.

Turns out she and her family started the museum in their home when they returned to Granada from France, where their ancestors had fled when the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492. Since she and we were all fluent in French, we switched from Spanish to have a deeper conversation. She’d decided to live in Granada and establish the museum because she was furious that she couldn’t get an academic supervisor or grant to fund a thesis on the history of the Jews of Granada. They told her it wasn’t an interesting topic, since no archaeological traces of the Jews remain.

Antisemitism still runs deep in the city. In fact, to this day, on January 2 every year they hold a parade celebrating the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. The museum had to give up on having directional signs to its location because they were constantly being vandalized; even smeared with feces. When they complained to the mayor, they were told that people could use Google maps to find them, so there was no need for signage.

From the 50,000 Jews who lived in Granada at its peak, before the 1492 expulsion, there are now only four Jewish families, who returned when Spain decided to admit that the expulsion had been a bad idea and invited Jews back a few years ago.

People always talk about how Jews and Muslims, as fellow “people of the book” had traditionally got along well, and certainly in Granada relations between the Jews and the Muslim rulers were good for much of the time of Muslim rule. Samuel Ibn Nagrella, for instance, become a key advisor to the first Ziri king in 1013. As always in Jewish history, there was resentment among some of the population when they saw how the Jews were prospering. Nagrella’s son, Joseph, took over after his death, and was not a good leader. Tensions exploded on December 30, 1066. Rivalling the worst of the East European pogroms that came centuries later, 4,000 Jews were murdered.

Nevertheless, conditions for the Jews under the Muslim rulers were better than in much of the world for several centuries, until “the Catholic rulers” (King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella) took up residence in Granada in 1492. Although Muslims were afforded some protection under the Treaty of Granada, things went a lot worse for the Jews. Ferdinand and Isabella ordered the destruction of the homes of 20,000 Jews to build a cathedral and hospital, and soon after ordered all Jews to leave the country.

I still struggle to understand why antisemitism has been so persistent, across countries, cultures and times. Although we have not come across it directly in Spain, the reality is that this country consistently ranks as one of the worst globally for antisemitism. In cities like Malaga, with its highly internationalized population, it is not common (or at least, not openly so), but it is much stronger in other parts of the country, including Madrid. According to the 2019 ADL Global Survey Spain has the highest percentage of the population holding anti-semitic stereotypes of all Western European countries. And the Covid conspiracy theories have been fuelling it lately. This is all particularly ironic when you consider that one in 5 Spaniards have Sephardic Jewish ancestry, according to genetic tests. If you include the Muslim Moors, the total goes up to about 1/3 of Spaniards who have either Jewish or Muslim ancestry. But it seems that Ferdinand and Isabella’s legacy still runs deep. Sad.

[…] you are there. Andalucía, for example, has many lovely mountain and beach towns to visit. Cordoba, Granada and Seville are just a short train or bus ride away from Malaga. In Guadeloupe, we decided to base […]