Call us spoiled (I admit it, we are), but we’ve seen so many different ecosystems in our decades of travelling that we wondered if it was really worth the expense and hassle of visiting the Galapagos Islands. Hearing about friends spending $20,000 for a Galapagos trip, we’d decided not to go.

But being in Ecuador for three months and not going to visit the Galapagos felt like a travesty. I feared that we’d regret it if we didn’t go. Getting to Galapagos once you are already in Ecuador is fairly easy and cheap. And while we are enjoying spending a chunk of the winter in Cuenca, Ecuador, and we might make it a regular part of our winter pilgrimage, we might not. If we don’t end up coming back here, I’d kick myself for having missed the Galapagos.

So we went. I’m glad we did.

Table of Contents

What’s So Special About The Galapagos?

As my DH pointed out, we’ve seen sea lions in California and British Columbia. We’ve seen iguanas in Mexico and Guadaloupe (where we even had some living in our garden). We’ve swum with sea turtles in Hawaii and snorkeled in what felt like a tropical fish aquarium in Akumal, Mexico. So did we really need to travel all the way to the Galapagos to see more?

In short, yes. Darwin had seen plenty of finches before he wrote the Origin of Species. Yet his five weeks in the Galapagos in 1835 were crucial in solidifying his theory of evolution. Evolutionary differences are clearly evident in many of the species found on the islands. Because the islands are so remote, the animals there have not only developed differences from similar animals in lands far away, but even from one island to the next.

For example, dome-shaped tortoises tend to keep their heads low to the ground, and are plentiful on islands where there is lots of low-growing foliage. Saddleback tortoises, on the other hand, have shells that rise in the front, making it easier for them to stretch their unusually long necks. They are prevalent on islands with less ground-foliage, so the animals had to stretch to reach food sources such as tree cactuses (which they can devour despite the spikes).

The saddleback tortoises use their long necks to establish dominance – he with the longest neck wins, and the others will back off. (Our guide at the Darwin Research Centre told us that some sneaky young ones will climb up on rocks or ledges before stretching their necks, hoping to trick others into thinking they are bigger than they really are.)

Marine iguanas are another animal that evolved to survive on specific Galapagos islands and are the only marine lizards in the world. They can stay under water for up to an hour.

Marine iguanas have flatter noses than land iguanas (adapted for feeding on marine algae), and flatter, wider bodies than other types of iguanas I’ve seen in places such as Guadaloupe. They also have flat tails that help them when swimming.

Another fascinating marine iguana adaptation: when food sources are scarce their bodies actually shrink! During El Niño hot weather periods the red and green algae that they generally eat disappears. Some of them can survive on brown algae but it is toxic to many and up to 90% of the population can die. Those that survive can shrink their body sizes by up to 20%. Not just their weight, but their length too! It seems that their bodies reabsorb some of their own bone matter.

Galapagos is also the hottest place with penguins. There are a few spots in the archipelago where cool marine currents at certain times of year make it possible for little penguins to survive. Galapagos penguins have smaller bodies than penguins elsewhere (less surface area to overheat) and they are great swimmers.

There are plenty of other unique species, including flightless cormorants (found only on Fernandina Island and part of Isabela) and certain varieties of birds. I think birders would probably appreciate this aspect of the biodiversity more than ignoramuses like me, who simply say, “Oh, look at that pretty bird!” (That said, the Blue-Footed Boobies are recognizable even to me. I didn’t get a good photo of any, but we saw plenty. The Red-Footed Boobies can only be found on Genovese Island. I may have seen Nazca boobies, which are also quite widespread.)

It’s Not Just the Species; It’s How They Live

One thing which makes visiting the Galapagos special is that, on all the islands, the non-human animals take precedence. If a sea lion is blocking a footpath, you can bloody well wait till it decides to move. (Or, if is asleep – and they do sleep a lot – step carefully around or over it.) Even on the highway, drivers swerve or stop to avoid hitting slow-moving tortoises crossing the road.

The animals are completely unafraid of humans, and the government’s intense regulation and tracking of tourists is designed to keep it that way. The islands are mostly national parks, and you must have a naturalist guide with you for visiting most places.

Even Galapagos sharks are safe to swim with, as there is plenty for them to eat, so they don’t consider humans as a food source. (One of our guides ranted about the unfair reputation sharks got from Jaws! Globally only 9 people died from shark attacks in 2022 – only 5 of them unprovoked — and nobody has ever had a fatal encounter with a shark in the Galapagos.)

How to Visit Galapagos & Help the Local Economy at the Same Time

Most people visit the Galapagos islands on small(ish) cruise boats. Even the largest of them are puny by global cruise ship standards, having only about 100 passengers. Most of the cruises are smaller so they can navigate among the islands more easily. Many have around 16 passengers.

We looked at the prices for the cruises, and realized that it is possible and much cheaper to see many of the main sights doing land-based island-hopping. The cheapest way to do it is to fly to Santa Cruz and visit several tour-booking agencies to look for the best last-minute deals. This article is one of the best I’ve found on how to visit Galapagos on a Budget.

DH isn’t comfortable with the level of uncertainty involved in last-minute travel, and he found a small “multi-sport adventure” tour, which we decided to try instead. He figured that even if he wasn’t impressed by seeing more animals, he’d enjoy the cycling, hiking, snorkeling and kayaking. Turns out, he enjoyed the physical activities and the animals, and has no regrets about going.

Kayaking in Las Tintoretas (Isabela Island, Galapagos) we had to be careful not to hit the sea turtles swimming around us.

One aspect I hadn’t considered before going was the impact on the local economy. Particularly on smaller islands like Isabela and San Cristobal, our tour guides and hotel hosts repeatedly thanked us for supporting locals by touring in this way instead of via cruises.

Fees, Fees, & More Fees

One cost aspect you tend not to read about in articles about visiting the Galapagos is the fees. Every time you turn around there’s another small fee being collected. Make sure you carry plenty of small US$ bills with you, because most things can only be paid for with cash.

The fees don’t add up to a huge total (especially compared to the overall trip cost) but they waste a lot of time and are simply needless hassle. I’m convinced they are handled as they are to create employment.

Here are some of them:

- When you get to the Ecuador mainland airport (you need to fly from Guayaquil or Quito to get to the Galapagos), be sure to find the booth to pay the US$20 Tourist Card fee. We had flown in from Cuenca so we had to exit security, find the booth, line up for an hour to pay the fee, and then go back through security. If we hadn’t asked, we’d have missed our flight because you can’t board without it.

- When you arrive on your first island, you have to pay a US$100 Galapagos National Park fee. It makes no sense that they don’t collect this and the tourist card fee at the same time, since everyone going needs both.

- Every time you have to take a little skiff to transfer onto a bigger boat you have a $1 fee.

- Most (all?) of the islands charge an entry fee when you arrive. It was $10/person to enter Isabela, for example.

- To get to or from Baltra airport (the one that serves the main Galapagos island of Santa Cruz), you have to pay to take a bus or taxi to the ferry that connects Baltra and Santa Cruz, $1 to take a little ferry for a three-minute ride across to the other side, and a $5 fee for the bus to the airport.

San Cristobal Island

We decided to treat this trip as a Galapagos taster, so our trip was only 5 days, and included 3 islands. First up was San Cristobal, which was a great place to start. I think if you started in Santa Cruz (as most tourists do) you wouldn’t feel like you’d really entered another world in the same way you do on a less-touristy island. It helped that we were greeted by a super-friendly hotel manger, Tatiana Jijon, at the Casa Opuntia Hotel.

Sea lions pretty much run the place. They are everywhere!

The first afternoon we went sea kayaking above and among the sea turtles and fish. The second day we did a full-day tour of the north coast, stopping at a beautiful beach, visiting the iconic Kicker Rock, and snorkeling. (One visitor and an instructor went scuba diving, which would have been awesome if we had the skills and lungs for that.)

(Click the arrows or swipe right to advance the slides)

Our first night in San Cristobal, DH learned an important lesson: never take food advice from a teenage server. The fish dish he ordered wasn’t even recognizable as fish. I had an awful pizza, but I didn’t expect much since I’m allergic to fish and seafood, so waterfront locations are always challenging. The second night we found a good restaurant (Inti Garden) that makes fabulous thin-crust pizza and home-made rice pasta. DH complained that his portion of grilled fish was too big!

Isabela Island

Day 3 we boarded a 10-seater plane to fly to Isabela island, which is the least populated of the islands you can go to without being on a cruise. It has a population of about 2,000.

Our schedule only allowed for one day on Isabela. There were pink flamingos hanging out in a pond a block from our rustic hotel.

We kayaked in Las Tintoretas volcanic coves. Unfortunately neither the penguins nor the white-tipped reef sharks were around the morning we visited. Lots of sea turtles.

In the afternoon we cycled to the Wall of Tears (more on that below). We’d booked the cycling as part of our tour and they sent a guide with us. I’m not sure if that was a legal requirement, or if it just part of the local employment project, because there was certainly no need for a guide for that part and, unfortunately, he was new to the island and didn’t have anything to tell us about the place.

It was fun stopping to watch the giant tortoises cross the path. We also visited a beach, the Play de Amor (the beach of love), that the marine iguanas seem to love.

Our last stop before heading home was the beach near our hotel, where we enjoyed another beautiful sunset.

Santa Cruz Island

Santa Cruz Island has a completely different feel from our two previous spots. It has a population of about 12,000, and the main town of Puerto Ayora is designed for capital-T Tourism. Fancy hotels, restaurants and shops. The streets are lined with travel agencies offering last-minute tour deals.

We visited the Charles Darwin Research Station in the morning. It is fascinating to learn about the tortoise breeding program. It started in 1965, with the goal of saving the giant tortoise population on Pinzón island, and soon expanded to include Espanola, where there were only 14 tortoises left. Now it runs breeding programs for many of the islands.

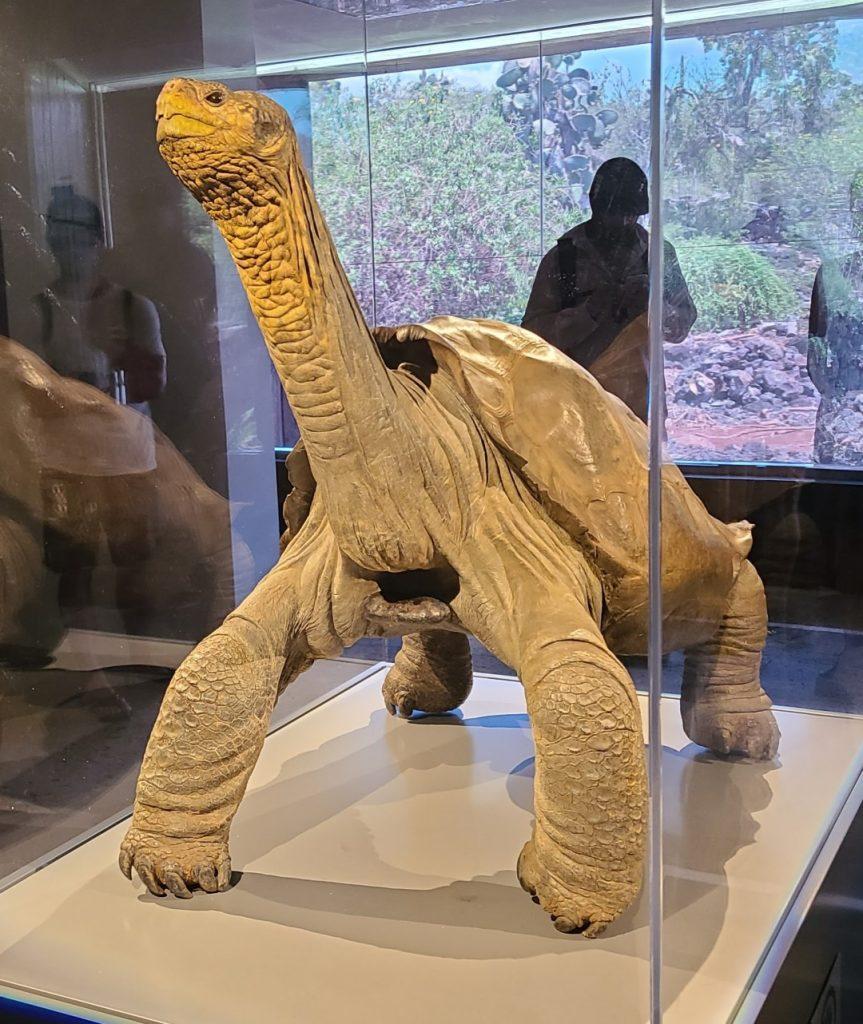

The most famous of tortoise of the Galapagos was “Lonesome George”, who was the last surviving one of his sub-species. The vegetation on his island, Pinta, had been ravaged by feral goats, and what were believed to be the last 3 known Pinta tortoises were captured for museums in 1906.

In 1971 Lonesome George was discovered. He was relocated to what became the breeding centre on Santa Cruz. Sadly, a massive global hunt failed to find a suitable mate for him. There were no Pinta tortoises left anywhere and none of the attempts to breed him with similar sub-species from other islands resulted in viable eggs. (Interesting tidbit about tortoises: the males can continue to father offspring throughout their lives.)

He died in 2012, aged ~100 (which is actually young for giant tortoises, which can live up to about 177 years and weigh up to 417 kg, or nearly 1,000 pounds). His body was preserved and is now on display at the research centre. Viewing it felt a bit like lining up to see Lenin’s tomb.

The tortoises on many of the islands became endangered due to a combination of:

- climate change and feral animals such as the goats, which reduced food supplies,

- predators that were not native to the islands (such as rats) which feed on the hatchlings

- natural predators such as large birds and snakes, which also feed on the eggs and soft-shelled newborns.

The breeding program takes the eggs and hatchlings and rears them until about age 5, when they are reintroduced to the islands they came from.

It has been a successful program, with the tortoise population on Floreana Island no longer needing protection, and others coming close to that point. (I wondered if mama tortoises grieve when their eggs or hatchlings disappear, but apparently they don’t generally stay with them after burying the eggs in the sand.)

In the afternoon we did another snorkeling and sight-seeing expedition. In addition to scads of beautiful fish, I finally saw a shark, and a blowfish. (DH had jumped off the boat into a group of hammerhead sharks during our San Cristobal outing, but they’d all wandered off before I hit the water.)

We also swam and snorkeled in the Grietas, a water-filled crevice between two volcanic cliffs. It has a mixture of salt-water from the ocean and fresh water.

The next morning we headed to the airport, where we spent much of the day because a bird had flown into the Avianca plane’s engine so the flight was cancelled. We did eventually get out on another flight, but so late that we weren’t able to enjoy the scenic ride from Guayaquil up to Cuenca, because it was dark by the time we got started.

Fiction Author Inspirations from Galapagos Trip

I often find myself imagining stories behind the people and places we see on our trips, so I’ve decided to start adding a section to my travel blog posts about some of the things that inspired ideas that may help me with my fiction writing, and might help you too, if you are an author.

Taking a Tiny Boat in the Dark

Most of the inter-island transfers take place early in the morning so tourists can have a full day of activities on the new island. The earliest by far was the day we had to be at the Isabela Island dock at 5:00 a.m.

Many of the people who gathered in the dark were locals, not tourists. Among them was a woman with two young children: probably aged about 4 and 7. They looked nervous and clung to their mother’s side. Each was dragging a small roll-on bag.

She could only bring two of the 3 bags down the ramp to load on to the small skiff at once, so she instructed them to wait at the top of the ramp. They stood obediently, watching her as best they could in the dim lamplight. A soldier finally realized she needed help and took the 3rd bag. When the mother came back up the ramp to collect the kids, the smaller one leapt into her arms with relief.

When we were all loaded into the tiny boat, looking into the wide-eyed faces of those two children, I couldn’t help thinking what it must be like for refugees, piling into dodgy, overcrowded boats in the dark, having to trust the mule who is transporting them illegally to an uncertain future.

When we transferred to the ferry a police boat pulled up and an officer came on board to inspect, making sure everybody had a life-jacket on (and ordering the captain to get child-sized ones for the little kids). I noticed that the police boat carried extra life jackets just in case. He also took a photo of everybody on board. All animal movements, including human ones, on the islands are carefully tracked.

Life on a Desert Island

We visited a couple of remote beaches, and could easily imagine what it would have been like for early sailors blown onto such islands and shipwrecked. (Ditto for the iguanas, who ultimately survived by learning to swim, eat algae, and shrink their bodies in times of food scarcity. See above.)

In Grade 7 our social studies teacher asked us to decide how we would organize ourselves if we were in such a situation. To my teacher’s horror, I said that the first thing the group should do would be to kill me. Since I’m deathly allergic to all fish and seafood, as well as to tropical fruit like bananas and coconut, I’d die soon anyway. Why waste resources on me? (I guess I must have been anticipating Piggy in The Lord of the Flies.)

The Wall of Tears

Imagine the inverse of a Siberian gulag. Instead of struggling to survive in a frozen wasteland (something we northern Canadians can easily relate to!) you are in an abusive prison camp on a remote island in the middle of the ocean. Galapagos islands had been used as prison camps a few times by the Ecuadorian government, and things never ended well.

The first prison colonies were set up on Floreana and San Cristobal islands in 1832 to imprison soldiers who had been involved in a failed coup. Conditions were so bad that the prisoners turned on their guards in a series of riots starting in 1837. Eventually they killed or co-opted them all. Various attempts to grow crops in the harsh conditions failed.

At the end of World War II, the government set up another penal colony, this time on Isabela. Conditions were atrocious, and to keep the prisoners busy they were ordered to heave stones to build a pointless wall. In 1958 the prisoners rebelled and killed the guards. The prison was officially closed in 1959.

I haven’t watched it in years, but the movie, Papillon, comes to mind. Some of the characters who appear in my upcoming novel, Red Rules, spend time in prison camps. Every little bit of inspiration helps!

Final Thoughts

In retrospect, I wish we’d done a slightly longer tour. If I were doing it again, I’d likely check out the last-minute deals and add a few days on a boat to explore some of the islands that are only accessible that way. Then again, given the challenge of my food allergies on a small boat, maybe I wouldn’t.

[…] Überraschungen bei den Transportkosten zwischen den Inseln, Regeln, die nur Barzahlung zulassen, und die Insel Besuchergebühren. […]

Great read. During my first trip to Cuenca, I was unable to schedule time to see the islands as it was work related. I’ll be returning for a month soon and found your tips and review very inspiring. I’m very excited to return and give the Galapagos a try!

Thanks for the feedback, Desmond. Have a great trip!

[…] We may go to the Galapagos, but that wasn’t the point of this trip. [UPDATE: We did go to Galapagos. You can read out it here.] As many of my regular readers know, one of our retirement goals was to spend the coldest six […]

Wow, $20k for a tour these days?! When I visited in 2004, a last-minute deal on a good ship was $1500 for a 7-day cruise, plus tips, airfare, and $100 Park entry. Lonesome George was still alive and trying, and Puerto Ayora was a sleepy little town, a fraction of its current size. I didn’t blog or tell anyone, so this isn’t my fault. 😃 It was a wonderful trip, but nowhere near $20k justifiable… that’s a lot of travel funds, or make-a-difference-in-someone’s-life funds. Amazing place, great memories, but I wouldn’t do it for $10k.

Thanks for the article.

There are certainly tours that cost less than $20K! But there are others that cost even more!

Thanks for the comment.

So interesting! I’m a birder and love wildlife, so I especially enjoyed your photos and descriptions of the birds, tortoises, iguanas, etc. BTW, that’s a Yellow-Crowned Night-Heron in your photo just above the title “It’s Not Just the Species.” We have them here in the U.S., too… but I’m certain the Galapagos Islands have many bird species I’ve never seen!