DH (Darling Hubby) is not a bus tour kind of guy. So I was surprised when he proposed that we do a group tour of Morocco. Although he’s traveled a lot, he’d never been to mainland Africa, and most of the other more adventurous places he’d been to were for work, so he had some hand-holding. Travelling in Africa on our own was something he wasn’t quite ready for. We bought and paid for a two-week Intrepid tour of “The Best of Morocco” in the era BC (Before Covid). A few days before we were to leave, Morocco closed its border due to Covid and the trip was scuppered. Now, three years later, we finally got to do it. I’m so glad we did.

Morocco is filled with contradictions: great beauty in its art and architecture paired with trash-littered roads and fields. Stunning, monumental palaces (the Royal family owns some 26 estates, including many grand palaces) and incredible poverty. (To quote the 2022 World Inequality Report, “Wealth inequality in Morocco is extreme: the top 10% of the population own more than 63% of the total, whereas the bottom 50% own less than 5%”.) A photo of the King and his wife wearing no head- or face-covering hangs in many stores and businesses, yet the few women working in those same businesses have nothing but their eyes (or at most their faces) visible. (Women, it seems, are allowed to work in kitchens and cleaning up after the tourists in hotels, but not as servers or in positions where they have direct interactions with the customers.) Bustling, modern cities, filled with many people living and working in medieval conditions. A huge tourism business, but an inability to provide reliable internet at hotels catering to those same tourists.

That last point is why I wasn’t able to post to this blog while travelling in Morocco, so instead you get one megapost, which will include some of the things I managed to post to Facebook during those moments when we did have Internet.

Casablanca

Despite the romance associated with Casablanca thanks to the eponymous movie, I would say skip it if you are short on time. It is a working city, and not a particularly beautiful one. My first reactions to Casablanca were: noisy, crazy traffic, dirty. Its main attraction is the Hassan II Mosque, which has the 2nd tallest minaret in the world, at 210 metres (690 feet).

After a little de-jetlagging nap we went to explore the Quartier Habous. I don’t know what drugs the author of the Bautrip website was on when s/he wrote “Quartier Habous is one of the most picturesque places in Casablanca. It’s a neighborhood of the city with a quiet marketplace. With no crowds, it’s considered as the new Medina of the city. The area is wide and well maintained,” In fact, the absolute opposite is true. Noisy. Crowded. Impassable, poorly maintained roads and sidewalks. Crossing roads, even with a green walk light, means death-defying acts. (Although a couple of drivers did stop and smile indulgently, letting me cross at times when I hadn’t dared to follow DH into the swarm of vehicles).

Despite the noise and craziness, I did enjoy seeing what is clearly a busy, local shopping area. I was fascinated by the dimensions on the mannequins: big butts, breasts and solid thighs. Who knows what the actual dimensions of the women here are, since almost all are hidden in long loose garments.

Later we met our tour guide, who took the group to a nearby spot for dinner. It was a fast-food joint which, theoretically, had many Moroccan standards but when we tried to order them, none of the Moroccan dishes were available.

Rabat

After a bumpy beginning in Casablanca, we took a train to Rabat. In theory our seats were numbered, but it took some persuasion on the part of our guide to convince the Moroccans to get out of our seats and let us have them. Apparently numbered seats on the train are relatively new, so people aren’t yet used to the concept.

Our first impression of Rabat was a stark contrast with Casablanca. It is clearly the seat of government: the capital city must be a shining star. It is clean, calm (mostly), the roads and sidewalks are well-maintained, and drivers obey the traffic signals!

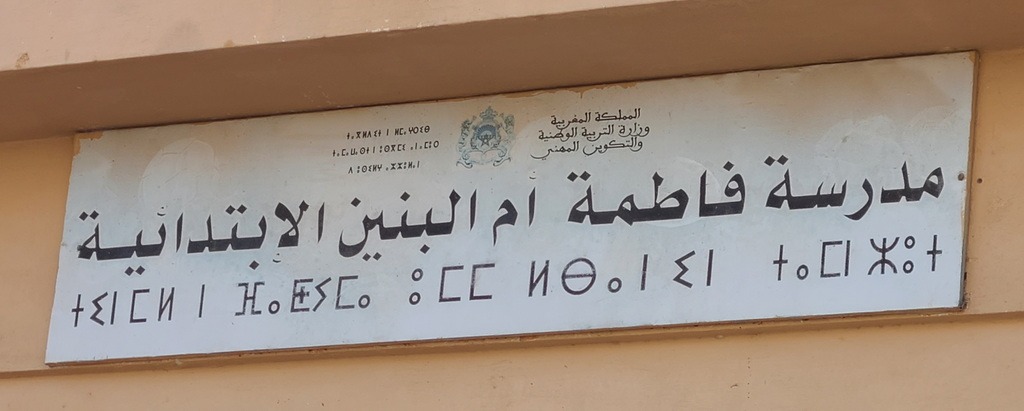

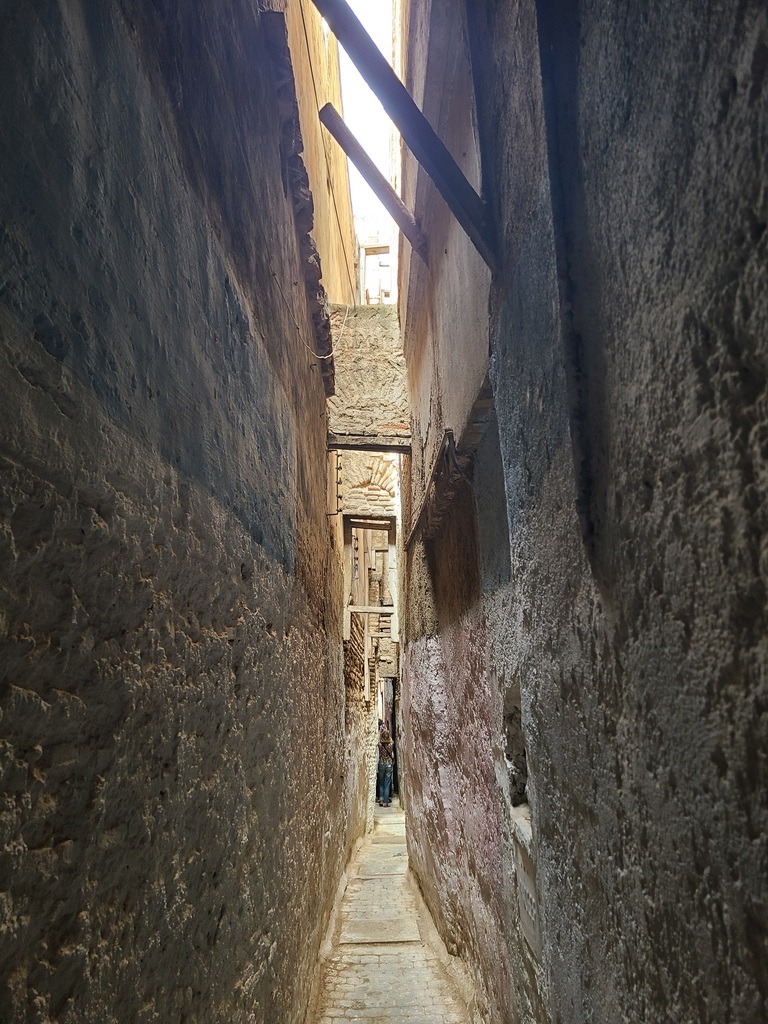

After taking in a bit of the modern city of Rabat we wandered into the old town and saw what was to be the beginning of two weeks of narrow alley-streets, small shops, and confrontation with realities such as the fact that 27% of the Moroccan population and a whopping 55% of women are illiterate, so there is still a demand for scribes.

Rabat is known for its half-built medieval tower. Begun in the 12th century, it was intended to be the tallest in the world when it was planned, but Sultan Yacub-al-Mansour died half-way through. By that point it was 44 metres, out of a planned 86. The current King is working on building a new tower which will be the tallest in North Africa.

Meknes

The real WOW factor of the trip kicked in on Day 3, in the stunningly beautiful city of Meknes. Originally created as a military settlement in the 11th century, under Sultan Moulay Isma’il it became the capital of Morocco in 1672. It is famed for the Cara prison, which could house up to 60,000 prisoners underground! (I hate to think about what that must have smelled like.) Designed by a prisoner who used his architectural services as a way to negotiate his freedom, it was built by slaves (mostly from other parts of Africa) and Christian prisoners of war.

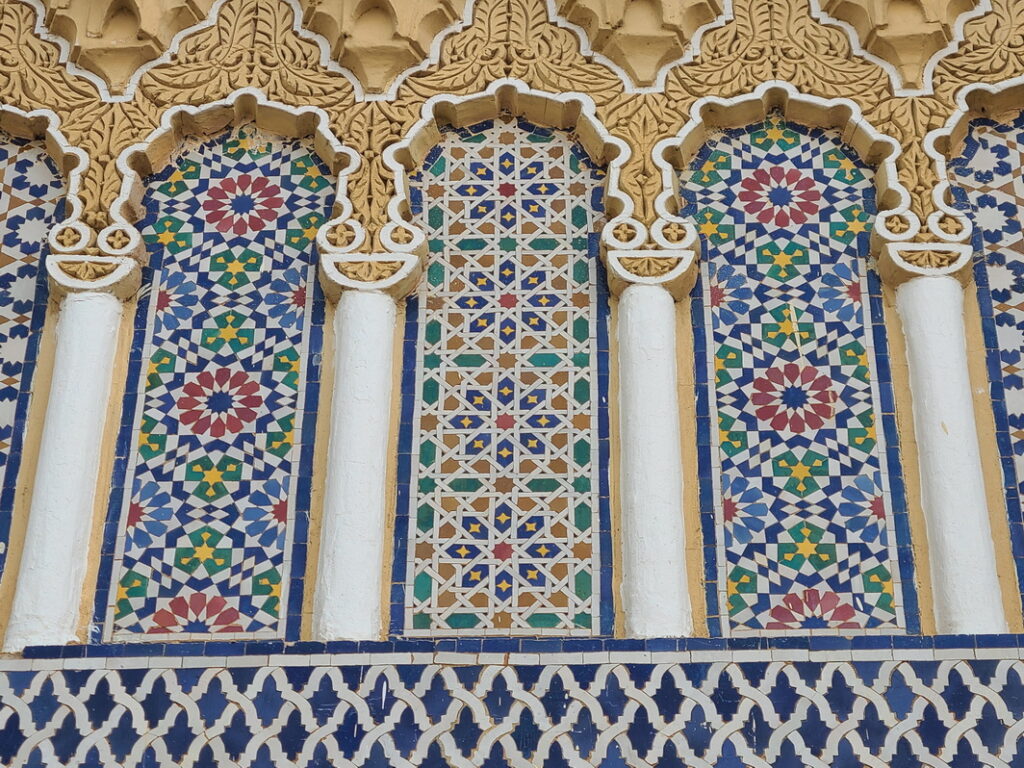

Each major city in Morocco has a signature colour. Meknes is green. You see it as the dominant colour in their mosaic decorations. (Casablanca’s is white — logically, if you think about the Spanish translation of the town name: White House). Marrakech is red and Rabat is blue.) The images below are from the Mausoleum of Moulay Ismail.

After visiting the Mausoleum we explored the medina (old city).

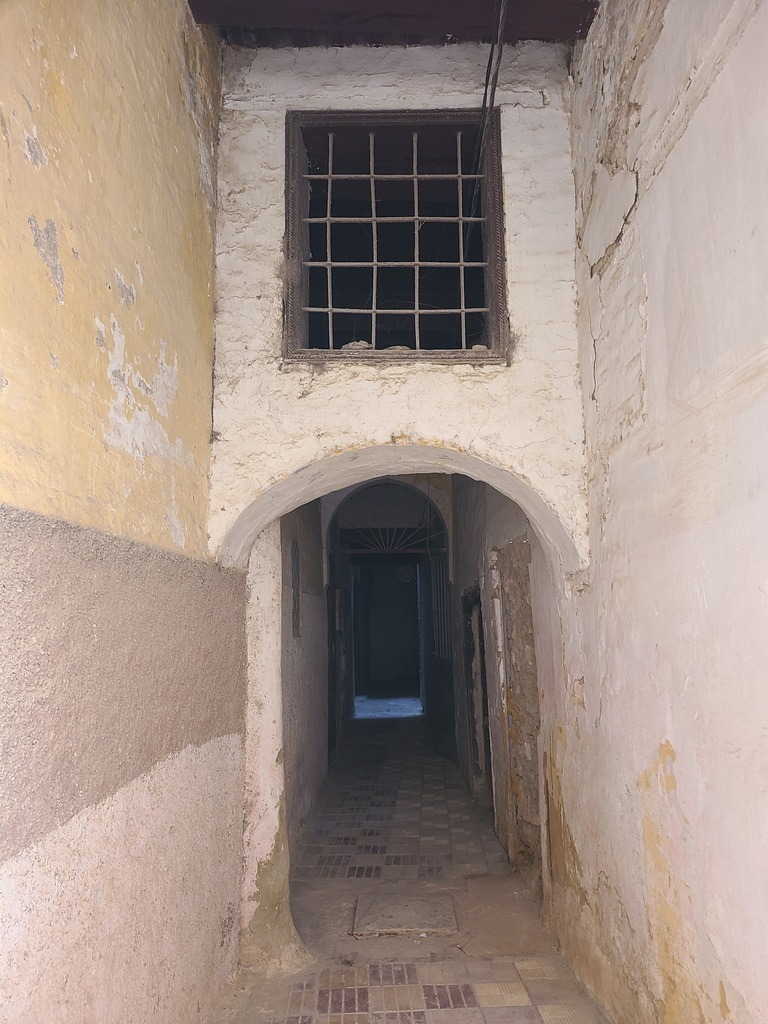

More narrow streets and doorways. Note the doors within doors. The smaller doors are for family. The larger one is opened for guests. (And/or large animals.)

Volubilis

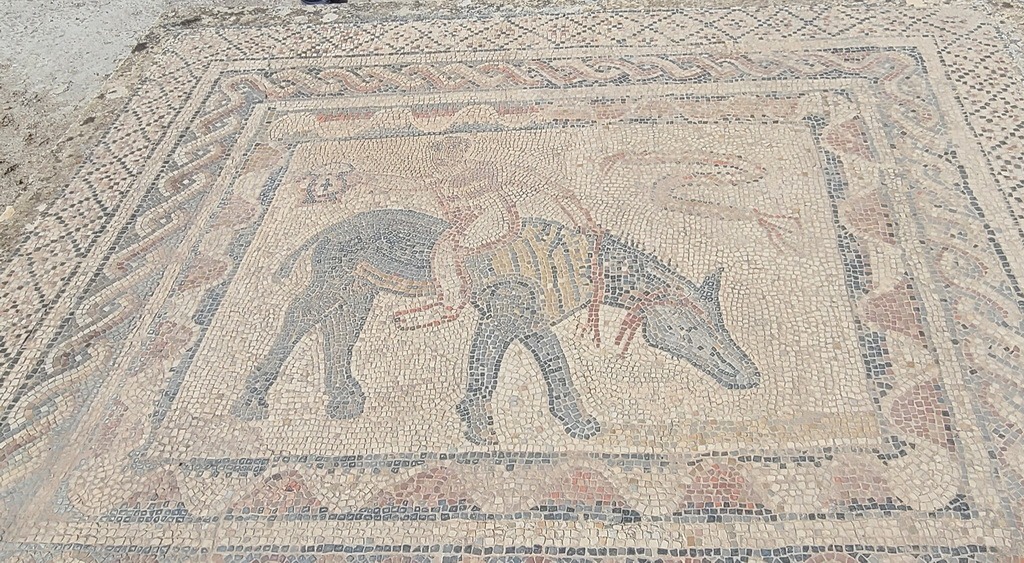

Volubilis was a sizeable city ruled by the Romans from year 40 to 300 CE. On a plain surrounded by good land, it exported olives and wheat. It also sent local lions to Rome for use in gladiatorial matches. Within the city walls there were some 60 villas; many of them enormous and with well-preserved mosaics, 3 public baths, a sewage system, wide boulevards including a triumphal arch (think Paris — Arche de Triomphe).

Fez (or Fes)

Fez is a spectacular place to see art and craftwork. Long famed as the centre for tilework, it is also well-known for the Chouara Tannery, which dates back to (some say) the 9th century (others say the 12th). The Moroccan government has made it a priority to maintain the craft traditions of the country. In the medina (old town) markets the government has agreed to keep vendor rents at what they were in the 1950s as long as the little businesses stay in the same line of work and continue to train and use the traditional methods. This is one of the few parts of the world where you can feel confident that the stuff you see in the markets is not made in China.

The Chouara Tannery

I read a historical novel last summer in which one of the characters worked in a tannery. He described the stench, which he could never get out of his clothes or body. Having now visited a traditional tannery, I understand why. They give you a sprig of mint to inhale as you walk through, because the smell is so overpowering. The animal skins are softened in vats filled with mixtures of cow urine, pigeon feces, quicklime, salt and water. And these people slave away, right in the vats, for hours every day!

As with so many things in Morocco, they struggle with the the dilemma of whether to preserve these ancient traditions, which are part of their history and bring in much-needed tourism dollars, or to sacrifice both traditions and jobs to preserve the health of the workers (and those affected by downstream pollution). The problem is, if they opt for the latter, how would they replace those sources of income?

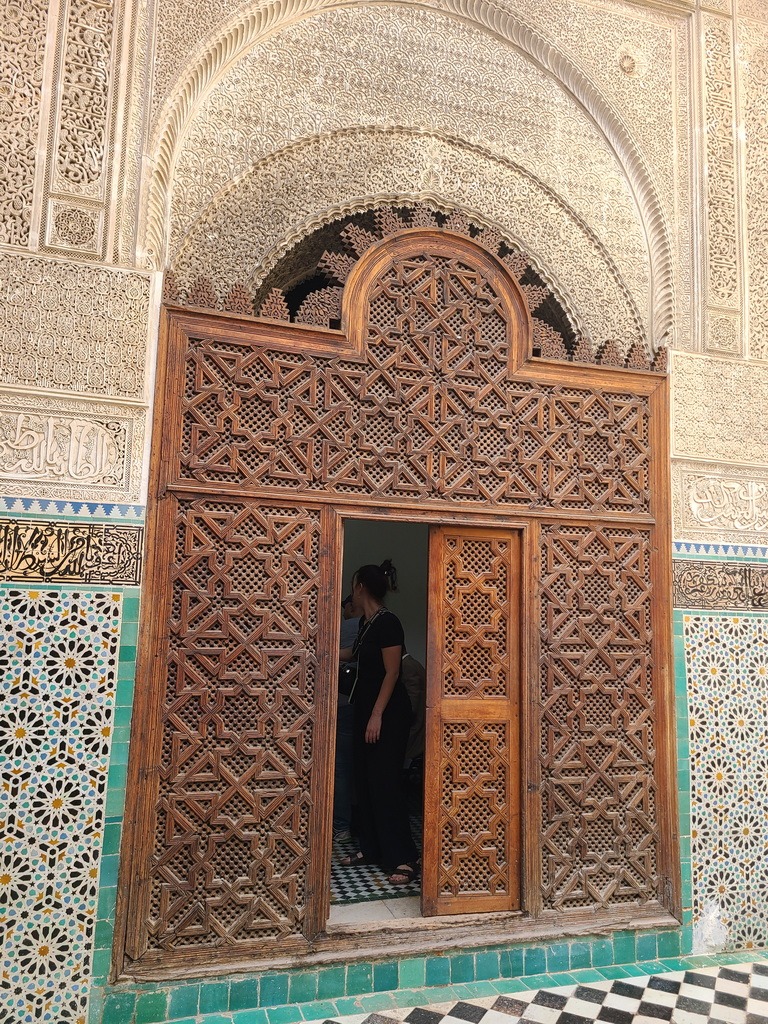

Bou Inania Madrasa

As with every city in Morocco, Fes also boasts beautiful architecture. Particularly lovely is the Bou Inania Madrasa. Built in 1350-55, it housed scholars from all over the Muslim world in its heyday.

Driving, Nomads, Picnics & Monkeys

As we rode along the highways we often passed groups of plastic-tarp covered structures. Turns out these are nomad encampments. The Moroccan government has offered the nomads housing, education and health care, but (according to our guide), they refuse it because they don’t want to give up the nomadic way of life. It’s a brutally harsh existence, but it is what they know and have done since time immemorial.

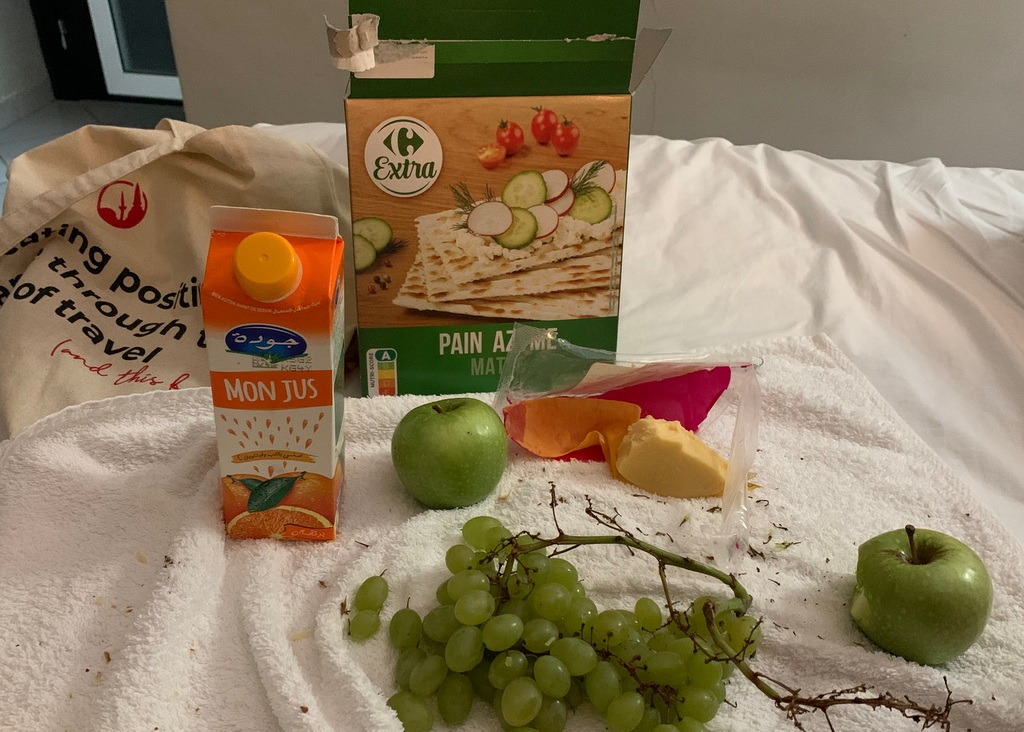

Before a long driving day we stopped at a big Carrefour grocery store to pick up food for a picnic. Worried about cross-contamination by allergens (nuts or sesame), I was surprised to find a box of matzoh in this Muslim country at a time of year that isn’t even close to Passover. I figured it would be safe for me. It was. Others on our tour also appreciated it when they were struggling with dysentery.

Atlas Mountains & a Berber Home

We continued our journey through the desert and into the Atlas Mountains. Along our way we stopped at a roadside stand for fresh pomegranate juice, looked into the valley where most of Morocco’s dates are grown, and visited a Berber village, including having tea at the home of one of the residents.

We managed to get to the village without being caught in the storm. Leading into it is a beautiful gorge. Thinking (incorrectly) that maybe it was the famous Todra Gorge, someone on our tour asked some local kids what the gorge was called. They shrugged. It’s simply “the gorge that leads to the village”.

As with many mountain villages, living conditions are not much different from what they would have been hundreds of years ago. Berber houses are traditionally (and most still are) made from packed mud, mixed with straw and sometimes small stones. Much to the irritation of our tour guide (who grew up in the High Atlas mountains), many have now started using breeze block construction, which is faster and easier to build with but makes no sense because it doesn’t insulate well, so it gets bitterly cold inside in winter and too hot in summer. This village was mostly of the traditional kind, but you can see in one of the photos that a recent breeze block building was going up.

It was apple harvest season, so all the men (except the very old) and women who didn’t have young children were off working in the harvest. So it was a village filled with the very old and the very young.

The homes do not have plumbing. A couple of women in our group urgently needed to use “the facilities”. At first our host simply shook her head, no. When they insisted, her daughter led them through the village to the pit where donkeys were shitting. I suppose in their homes residents use chamber pots, which they dump there.

Most homes do, however, have TVs. Our guide noted that TV is important to let people know what’s going on in the world outside their villages. In the first few months of Covid, the nomads had no idea that there was a plague spreading throughout the country. But they soon discovered that the price they could get for selling their sheep and goats had plummeted, with the closing of tourism. Alice Morrison, author of a recent book on her trek with nomads, said she witnessed them bringing livestock to local grocers and begging them to take the animals in exchange for essentials, such as sugar, tea, and flour.

I was distressed that our “host” didn’t join us. When the tour brochure talked about having afternoon tea with locals, I hadn’t imagined them bringing in the tea and breads, then sitting at the back of the room watching us. I had hoped we’d be able to have some conversation and learn about their lives. Our tour guide is Berber, so language wasn’t the problem. I’m not sure what was.

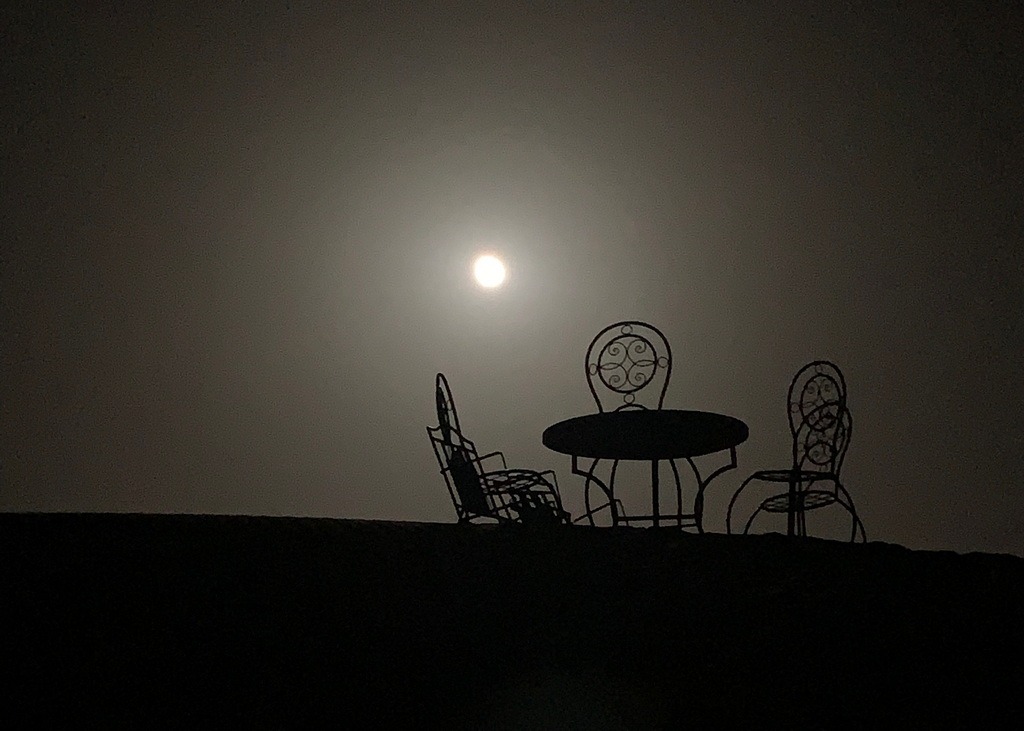

Sahara Desert

By the 5th day of our trip, several people on our tour were suffering intestinal problems. Mine, sadly, hit the night we were camping in the desert. It could have been worse: there was at least a toilet to sit on. But there was no running water so you had to scoop water out of a barrel and pour it into the basin to try to get the waste to go down. I spent a lot of the night scooping water. I was not the only one, and clearly the staff are used to this: the barrels got replaced a few times during the night.

Despite that, I did enjoy the sunset camel ride (which I was still well enough to do, although I couldn’t go on the sunrise ride the next morning). My camel seemed happy enough to let me onto its back, but many of the camels complained noisily as people tried to mount them. Once the people were on board, the camels accepted their lot and walked calmly. I’m surprised animal rights activists don’t complain about this activity, although I suppose the camels wouldn’t still exist if they didn’t work for a living. (We were offered camel burgers at one point. Apparently that’s what happens to them when they get too old or ornery to work.)

Training a camel is a long process. It typically starts between ages two and a half to four, and it takes about two years before they join caravans like these. Female camels are only put to the work of carrying passengers if they are infertile. Camels can be both affectionate and temperamental. If you treat them badly during training, they will take revenge on you. Our caravan guide clearly had a close relationship with his camels. They kept nuzzling him, and he’d gently direct their focus back to the path they were walking.

After the camel ride we gathered in a collection of tents that served multiple tour groups, with a central open area for a fireplace and music for the evening. I was a bit surprised by the fact that one of the musicians was playing an electric guitar: hardly a traditional musical experience! But even so, the music was lovely. I watched some young, female tourists dancing and flirting with the musicians and realized that for them, this would be a magical night they will remember nostalgically for the rest of their lives. That’s one problem with having travelled as much as I have: you get a bit jaded and focus on the inauthentic instead of fully enjoying the moment. Ah, to be 21 again!

Atlas Movie Studios

The next day we had a choice of touring a colonial military fort or the Atlas Movie Studios, where films such as Cleopatra, Lawrence of Arabia, the Last Emperor and Black Hawk Down were filmed. We opted for the latter, and had a delightful tour with our guide and budding movie-maker, Abdo (aka thephotographerabdo on Instagram). He demonstrated some fun camera effects (see my supporting role as a door guard), as well as taking us on a trip through “China” (filming of The Last Emperor), ancient Egypt (Cleopatra), Rome (Gladiator), etc.

These studios are appealing to the moviemakers because:

1. Morocco can be made to look like many places in the world, without the dangers of those countries. The nearby Atlas mountains are a great stand-in for the Himalayas, you can get Afghan terrain without the wars, etc.

2. It is almost always sunny. Good for lighting, and the blue sky can be used like a “green screen” as a backdrop to fill in later with other scenery.

3. Labour is cheap and plentiful.

4. The locals can look Middle-eastern, Roman, Greek, etc. Our guide told us the only film for which they had to import extras was Kundun, because they can’t make Moroccans look Chinese. They flew in 300 extras but forgot about chopsticks, and soon discovered that it is almost impossible to eat couscous with chopsticks!

5. There is no extraneous noise. There’s only one flight a day that goes anywhere near here, and no trains, people, or traffic noise anywhere near the studios.

Ait Benhaddou

More movie filming takes place in the Unesco World Heritage site of Ait Benhaddou. (Some of Game of Thrones was filmed here.)

To be continued…

[…] To see Part 1, go to https://temafrank.com/morocco-the-good-the-bad-the-ugly-the-beautiful/ […]

This was SO interesting, and I loved all the photos (and videos). Morocco is a place I doubt I will ever visit in my lifetime; I enjoyed being an armchair traveler!

Fantastic photos and information/insights. Happy travels, you two!

Thank you, Cynthia!

Thanks for the comment, Peggy. I didn’t have the courage to go to Morocco as a single woman in my early 20s!

I was 23 when I hitchhiked in Morocco, spending most of my time in Fez. It was like stepping into the Bible. You’re right that these experiences at a formative age are with you for the rest of your life. Your visit sounds wonderful, thanks for sharing it.