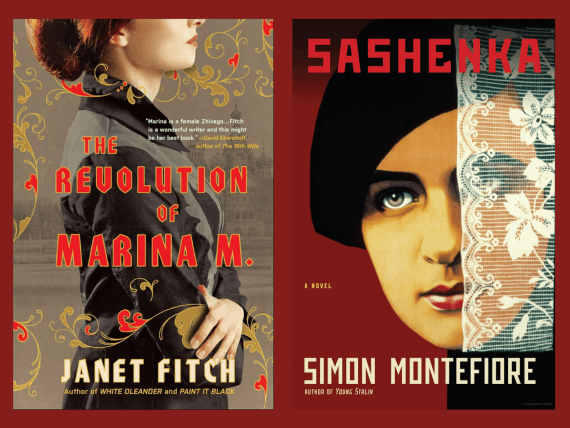

When I started reading Sashenka, I looked to see who had written their story first: Simon Sebag Montefiore or Janet Fitch, with her novel, The Revolution of Marina M. (The answer is that Montefiore’s book predates Fitch’s by nearly a decade.) Both had early scenes of a spirited, upper-class girl leaving her private school at the end of a day and being picked up in a fancy carriage on a snowy day. In both novels, the girls get into trouble with the Czar’s secret police shortly before the Russian Revolution because they’ve been hanging around with the wrong sort of people — i.e. revolutionaries. And both meaty books are enjoyable, engrossing reads demonstrating a depth of research and knowledge about the time and place. I recommend both of them.

Fitch’s novel stays in the early revolutionary period, and brilliantly evokes both the time and the behaviour of a smart, precocious teenage girl. We see her evolve, giving up her comfortable existence to live among the revolutionaries and try to change the world. Marina is a wonderfully complex character. At times I wanted to shake her and yell “Don’t do that!” but even her bad moves were totally believable, with results that were excruciatingly painful.

Montefiore’s strength is in his incredible knowledge of the history. Without being heavy-handed, he brings you into the politics of the period, all told through an interesting story. I felt that the first section of the novel was the best. He later skips ahead to the period after the worst of Stalin’s excesses and shows the young girl now as a mother and Party loyalist. Unfortunately, this is where it became clear that the story was being told by a man with little true understanding of women. SPOILER ALERT (Skip to next paragraph to avoid spoiler): Montefiore has a passionate affair develop between two characters with no apparent reason for why the woman would be attracted to the man. The male character was rude, homely and totally lacking in charm. There was nothing in the setup to justify why she would have even a brief fling with him, let alone see him as the great love of her life.

I kept reading through to the end of Montefiore’s book because, apart from his lack of understanding of women, it was a good story, and it accomplished the goal of immersing the reader in difficult times in the history of the Soviet Union. The same sort of gruesome, painful scenes that Fitch had in the abusive relationship between Marina and a man who both intrigues and tortures her, Montefiore had in the interrogation rooms.

I don’t know if a man reading the two books would react the same way I did. Overall, I give Sashenka a 4/5 rating for the strong history and many beautiful metaphors and similes. It is part of a trilogy, but I have not yet read the others. I’m too busy trying to finish my Russian Revolution novel, Red Rules. I give The Revolution of Marina M. a rare 5/5. It was so good that, although I’ve bought it, I decided not to let myself read the 2nd book in her series until I’ve finished writing Red Rules: I don’t want to risk being unduly influenced by Fitch’s exquisite writing. Luckily, my protagonist is not an upper-class girl stepping into a carriage on a snowy day, so I’m probably safe.

[…] to keep me wondering is a sign of great writing.As with the previous novel I read by Montefiore, Shashenka , I feel that the main weakness of this one is the author’s lack of understanding of women. As […]