Like most historical novelists, I can easily get distracted for days at a time by researching some little fact that I want to be sure is correct in my novel. Today’s rabbit hole is brought to you by the fact that my protagonist – like my grandfather who inspired the story — is named Borukh.

My grandfather, Boruch, went by Benny or Bennie in Canada and the US. Sometimes he also alluded to himself as Boris, as in when he changed the lyrics of Rock-a-Bye Baby. In his version, it ends not with “Down will come baby, cradle and all” but “Down will come Boris, breaking his skull.” I’m thinking his childhood in Russia may have left him with PTSD.

(This picture is of my daughter, not Boris, but I couldn’t find a suitable picture of a baby hanging in a treetop. Despite her best toddler efforts, she did not break her skull. Although she did end up with a scar under her chin from trying to climb over the back of a toddler rocking chair. This is the same kid who now does arial gymnastics and rock climbing for fun.)

Because many Jewish prayers start with what we transliterate as Baruch ata Adonai (Blessed are You), some people who’ve read parts of my novel complain that I’m writing the name as Borukh rather than Baruch (or Barukh). These are all probably just different transliterations of the same word, since it would have been written in Hebrew, Yiddish, and on official documents in Russian, none of which use Latin script. Boris vs Barry, perhaps?

When he translated his name upon arriving in America, he called himself Bennie, and later Ben. Those, per his daughter (my mother) would have been a variant of Benedict, which means Blessed. That brings us back to the prayer, but doesn’t resolve the a vs o debate.

My investigation of how to write his name in the novel led me to the JewishGen Belarus database. There I found a list of the main businesses in Minsk in 1902. (My grandfather, Borukh, was from a town outside of Minsk. He moved to the city itself in 1905). Looking at the business owners’ names, 12 of them were Borukh (or someone who was the son of a Borukh). There were no Baruchs or Barukhs.

Turn of the Century Business Owners in Minsk

That led me to more interesting tidbits. At the time, about half the population of Minsk was Jewish. Since Jews were barred from most professions, they were the tradespeople: 92% of the businesses were owned by Jews. Of the 349 businesses in the list, Christians owned 25 (including all four sausage stores), Muslims owned two (a gold & silver shop, and a bakery), and one musical instruments shop was owned jointly by a Christian and a Jew.

Types of Businesses

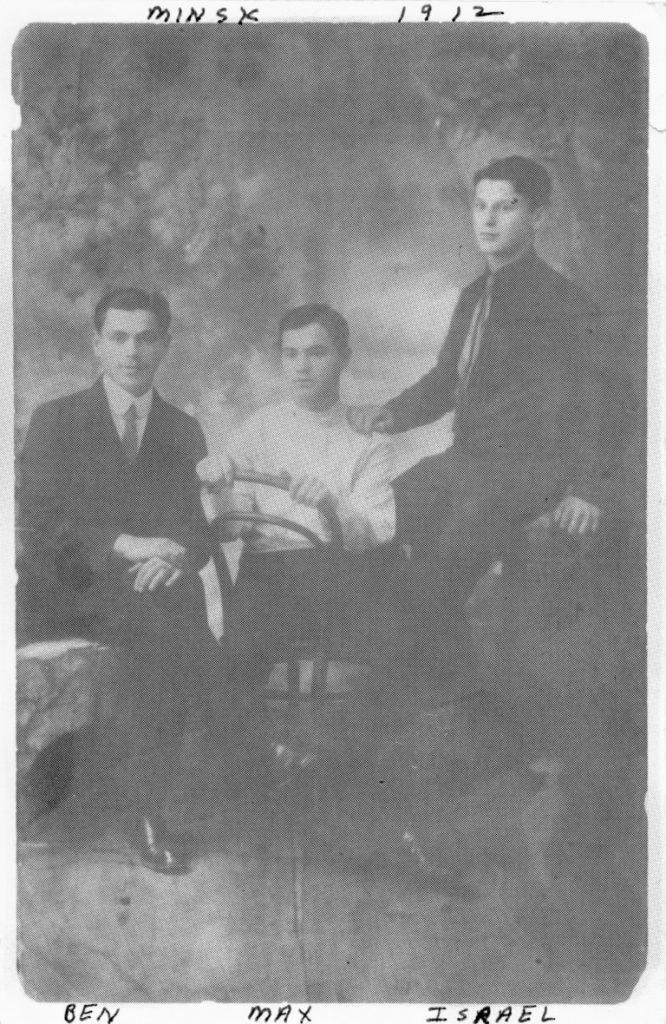

Even though 1902 was still early days for commercial photography, there were 9 photo studios in Minsk. Here’s a photo of my grandfather and his brothers, taken in one of them. (Or possibly in one that started a bit later.)

The most common types of business related to making and selling clothes (fabric, haberdashery, boots, dresses) and grocery stores. Bank offices were next in line, with 20 of them. It was a literate population: there were 11 book stores, 10 publishing houses (some quite large), and three book binderies.

Most unusual type of business: a “stubble factory”, with 25 employees. Do any of you know what that would have been?

The list also told me what streets the businesses were located on, which is helpful to build a mental map of the town. Unfortunately, many of the street names changed after the Bolsheviks came to power (and often again in Stalinist and later times), so it isn’t a simple matter to plot them on a map. This is the point at which I, as a historical novelist, have to ask myself, “Do I really need to spend my time doing that?” Or should I climb out of this rabbit hole and get back to editing? Since I’m in southern Spain at the time of writing this blog post, I’m going to take neither option: I’m going to the beach!